“The best black, gay, one-eyed junkie piano genius New Orleans has ever produced”

There are certain people so musical that everything they are is musical. Their movements, their voice, their atmosphere. James Booker was one of those people. Not that he wasn’t a truly colossal pain in the ass to those around him, but the fact that many stayed with him and attempted to help his journey through this world pays testament to their appreciation of his genius. In a film, Bayou Maharajah, comprised of great interviews, fascinating recordings, amazing clips (from local bars aplenty to German TV) and some wonderfully eerie black and white “ghostly” videos, this original native son of New Orleans vividly grabs your attention. His voice, talking or singing, is hypnotic. His piano playing… well, that defies description. Neither “standard” Professor Longhair derivation, nor straightforward funk ’n’ boogie, but a weird hybrid of these things with a dash of Liberace’s romanticism (don’t laugh), and Chopin and Rachmaninoff’s melodies. There’s a distorted improvisation that slowly turns into “A Taste Of Honey” that somehow deepens a piece of pop fluff right in front of your ears. And always – always – something bitter and sweet mixed in. Often you watch him play an outrageous passage with a hard glint in his eye, a steely focus and drive, and as he ends it, a sly, shy smile to himself, as if to say, there, that’s what I can do… My favorite interviewee (and there are some great ones) is Harry Connick Jr., who knew Booker as a slightly wayward uncle figure (well, more than slightly) since Harry’s father, the district attorney of Orleans Parish, had befriended and helped Booker at various times. His recall of the night that Booker phoned him at two in the morning to ask Harry to come rescue him from some drug escapade gone wrong (“James, dude – I’m twelve years old!”) was extraordinary. He tells of recording Booker’s phonecalls, and you can see that he’s still unsure to this day why he did. He says something along the lines of I just loved hearing him talk, and I thought if I taped him, I’d always have his voice to listen to. Watch as Harry shows, beautifully, how Booker added layer upon layer of complexity to a tune. Mesmerizing.

I’ve found my harmonica, Albert…

Bathed in the warm glow of Bob’s band, a Dylan concert to really enjoy. Charlie Sexton still has the moves of a heart-throb (let’s not forget that he fronted the bar band in Thelma & Louise), Donny Herron’s like a young engineer at his desk, working tirelessly on all manner of instruments and sounds, and the New Orleans engine room of George and Tony just keeps rolling on, making even the most ordinary twelve-bar come to life. Yes, it had its up and downs. Michèle, up until then an enthusiastic applauder, said I’m not clapping that… after a particularly calamitous “Spirit On The Water.” I was with her – it was like a drunken showband at the end of the pier, with Les Dawson on piano. But the high points were high. A malevolent “Pay In Blood” that far surpassed the studio take. A great re-visit of “All Along The Watchtower” with a left turn, two-thirds through, into a spacey and atonal breakdown, before a thunderous climax. A lovely “Waitin’ For You”, a song written for the soundtrack of Divine Secrets of the Ya-Ya Sisterhood, highlighted by a Sexton solo that sounded for all the world like the great Grady Martin. A gorgeous “Forgetful Heart”. Oh, and a beautiful and soulful “Blowin’ In The Wind” to end with.

Good Vibrations

It’s the story of Terri Hooley, godfather of Belfast punk (he started a record shop called Good Vibrations) and it’s nominally a feel-good music film, but is actually pretty hard-nosed about the difficulties of Belfast in the 70’s. The fast-cut collage that follows the opening scene takes our main character from Childhood to 1976. It’s brilliantly done, in a kind of kinetic pop art way, packed with news images of the Troubles, and edited to Hank Williams singing “I Saw The Light”. As it progresses it becomes more and more distorted, and finally the song disappears among swirls of echo, to be replaced by a hum of feedback and soundwash.

Mel Brimfield, 4’ 33” (Prepared Pianola for Roger Bannister).

Strangest piece of art owned by We The People, seen on a short tour of the Government Art Collection. [4’ 33”, a 1952 composition by US experimental composer John Cage (1912-1992), is referenced in the title but not played. The actual score for the pianola takes as its starting point athlete Roger Bannister’s performance in the 1952 Helsinki Olympics where he came fourth – the race that spurred him on to his sub 4 minute mile].

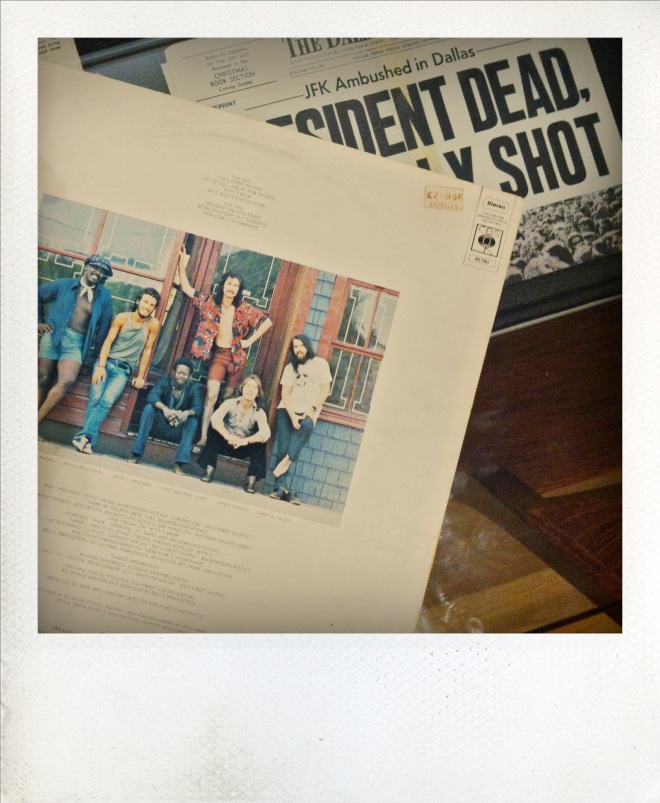

Bruce Springsteen, New York City Serenade, Rome

I remember a night in Sheffield, in 1974, when my friend Mike and I played this track (newly released) to Colin Graham, old family friend, editor of Angling Times, and big-time “Jazz Buff”. We were trying to prove that rock musicians could play their instruments and felt the combo of Bruce and David Sancious was a good bet… or something like that. In a game of what Charlie Gillett would turn into Radio Ping-Pong, we were searching through the records we’d brought with us (oh for an iPod) for something that we thought could pass muster. I wish I could recall what Colin, pipe in mouth, thought of it. Watching this recent performance of it, beautifully filmed and played, gives a Proustian rush back to the time I spent obsessively listening to The Wild, the Innocent & the E Street Shuffle. Apparently I bought it at Dobells, and it was £2.99.