School’s Out (For Ever?)

“Baby taking her GCSE’s. Passing of time is wonderful. Means never again I will hear a school choir sing I Believe I Can Fly. Thank Christ.”—Alison Moyet on Twitter. Amusing that R. Kelly has written the modern school anthem of positivity & inspiration—may I humbly suggest that all schools now switch to R. Kelly’s Relief. Great, great tune, beautifully covered by Sam Amidon as a folk ballad, has that anthem thing going on, teeming with hope, if not quite actualité.

“The storm is over, and I’m so glad the sun is shining

Confusion everywhere, without a clue on how to make things better

A toast to the man upstairs, ’cause he puts the pieces back together

Now let’s step to a new tune, ’cause everything is o.k.

You’re alright, and I’m alright, well, let’s celebrate.

What a relief to know that—we are one

What a relief to know that—the war is over

What a relief to know that—there is an angel in the sky

What a relief to know that—love is still alive”

Imagine a hundred ten-year-olds singing that.

Nostalgia Time 1. Mixing Buddy Guy And Junior Wells, Vanguard Studios, NYC, 1968

Sam Charters has been staying with us and I managed to find some pictures, among them this gem—a Three Track Machine (cutting edge, apparently), a vacant studio in Midtown, a twelve year old wannabe engineer.

The Poetry Of Aaron Copland

Came across this great piece I’d ripped out of the New Yorker years ago, by Alex Ross: “There is an affecting recording of the elderly Copland rehearsing Appalachian Spring with the Columbia Chamber Ensemble. When he reaches the ending, an evocation of the American frontier in ageless majesty, his reedy, confident Brooklyn voice turns sweet and sentimental: ‘Softer, sul tasto, misterioso, great mood here… That’s my favourite place in the whole piece… Organlike. It should have a very special quality, as if you weren’t moving your bows… That sounds too timid. It should sound rounder and more satisfying. Not distant. Quietly present. No diminuendos, like an organ sound. Take it freshly again, like an Amen.’ Copland conjures a perfect American Sunday in which the music of all peoples stems from the open doors of a white-steepled church that does not yet exist.”

For Emily, Wherever They May Find Her

From thetrichordist: Recently Emily White, an intern at NPR All Songs Considered wrote a post on the NPR blog in which she acknowledged that while she had 11,000 songs in her music library, she’s only paid for 15 CDs in her life. Our intention is not to embarrass or shame her. We believe young people like Emily White who are fully engaged in the music scene are the artist’s biggest allies. We also believe–for reasons we’ll get into–that she has been been badly misinformed by the Free Culture movement. We only ask the opportunity to present a countervailing viewpoint.

David Lowery [Camper Van Beethoven, Cracker] wrote this open letter. It’s worth reading. Here’s an excerpt:

“The existential questions that your generation gets to answer are these:

• Why do we value the network and hardware that delivers music but not the music itself?

• Why are we willing to pay for computers, iPods, smartphones, data plans, and high speed internet access but not the music itself?

• Why do we gladly give our money to some of the largest richest corporations in the world but not the companies and individuals who create and sell music?

This is a bit of hyperbole to emphasize the point. But it’s as if:

Networks: Giant mega corporations. Cool! have some money!

Hardware: Giant mega corporations. Cool! have some money!

Artists: 99.9 % lower middle class. Screw you, you greedy bastards!

Congratulations, your generation is the first generation in history to rebel by unsticking it to the man and instead sticking it to the weirdo freak musicians!”

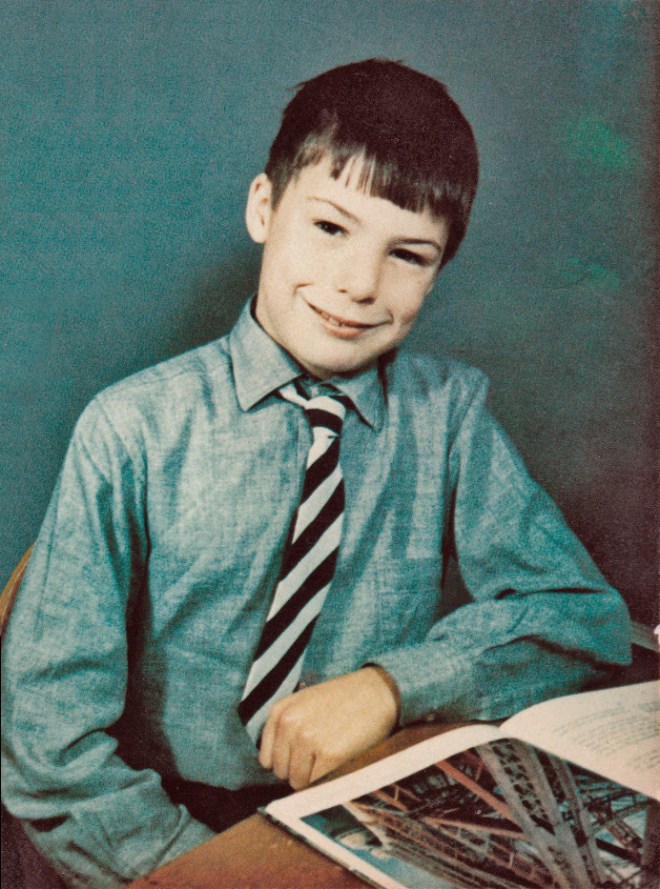

Nostalgia Time 2. Sid Vicious Stole My Corgi Toys

Nah he didn’t. But the Punk Britannia series on BBC4 put me in mind of Simon, as I knew him—John Simon Ritchie—an extremely nice playmate. My mother’s friend Rene was Anne Beverly’s sister and was often called on to help a fairly troubled woman navigate her messy life. We lived in the same block as Rene and her son David, and Simon—a shy kid— spent time there, when the need arose. I remember long afternoons spent on our hands and knees with Corgi cars in David’s tiny bedroom… At some point he stopped coming round to play and we all moved on to other things. I saw Simon twice more. Once on Shaftesbury Avenue, looking in the window of a music shop, long greatcoat, hair cut like Bowie, fidgeting, mumbling, smiling. And then as Sid, on a tube train—summer of 77 I’m guessing, definitely a member of the Pistols—leather and chains, when I felt too intimidated to say anything, but we exchanged a glance and sort-of-knew that in some previous life we had known each other.