I’m re-publishing this following the passing of one of my favourite “Dylan” photographers. It was originally written for Pulp magazine in 2017.

Bob Dylan: A Year and a Day. Photographs by Daniel Kramer

Edited by Nina Wiener / Art Direction by Josh Baker / Design by Jess Sappenfield

Published by Taschen, hardcover in a clamshell box, edition of 1,965 (cute!)

“In retrospect, it’s clear that Bob was in the process of winding up a very large spring. I didn’t know then how much of that spring would be let loose in the coming months.” – Daniel Kramer

On July 20th 1965, Bob Dylan, the star of the Greenwich Village Folk Boom, exploded onto the pop charts. America’s first modern singer-songwriter, Dylan, in the six minutes and thirteen seconds that it took for the epochal “Like a Rolling Stone” to be debuted on US radio, virtually created grown-up rock music. But Dylan’s spectacular reinvention of himself and his music had not just happened overnight – it had been brewing for a while. At the beginning of this astonishing, game-changing period – the like of which had previously been the preserve of fine artists such as Matisse and Picasso – photographer Daniel Kramer found himself, through a mixture of talent, persistence and chance, in the position of recording the highs of an extraordinary year in the life of Bob Dylan.

Having first seen Dylan on Steve Allen’s variety show in February, 1964 (“It was the kind of sound I always liked. It reminded me of a voice from the hills… like a voice that had been left out in the rain and rusted…”) Kramer decided that he had to photograph this performer who was brave enough to play songs about social injustice on a mainstream tv show. He called Dylan’s management: “Naturally I was told Mr Dylan was not available. And so it went. I would call, and they would say no.” Eventually, Dylan’s manager, Albert Grossman, picked up the phone. “By this time he knew why I was calling. I convinced him that I was a reasonable, completely sane, published, professional photographer. I was caught by surprise when his almost immediate answer was, Okay, come up to Woodstock next Thursday. You can have an hour. Just like that… just like that!”

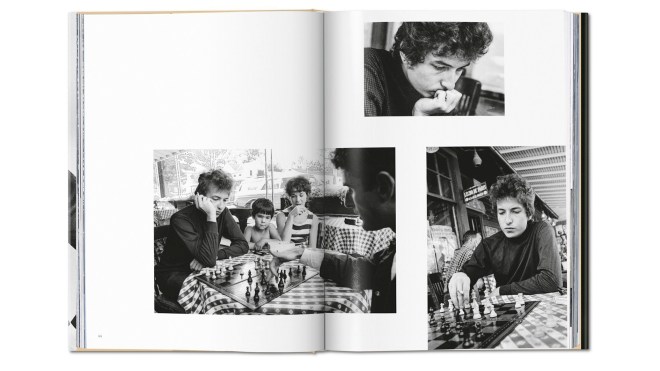

So Kramer drove two hours north of New York City on a bright August morning and spent the day following the 23-year-old musician as he read newspapers, played chess, and hung out with Sally Grossman (Albert’s wife) and his own wife-to-be, Sara Lownds. In the early Sixties, Woodstock was still a sleepy burg, a place where Dylan could keep the increasing intensity of life in New York at bay. The pictures are winningly relaxed and goofy, Dylan obviously finding Kramer a copacetic presence, and from that simple beginning, Kramer found himself photographing Dylan on thirty occasions over the next 365 days.

Kramer had come to photography early, aged 14, and later fell into a job working as an assistant at the studio of the fashion photographer Allan Arbus. “His wife, Diane Arbus, also did her darkroom work there – it turned out to be more than just a job. From Allan I learned to manage a studio, work with models, and run the business – and from Diane, I learned to open my eyes a bit wider, to think about my pictures in new ways.” His next gig was assisting Philippe Halsman, legendary Life magazine cover photographer. “From Philippe, I learned how to make light do your bidding, instead of the other way around, and how to choose a decent wine – and that photography could be a great adventure and a pathway to the whole world.”

From Kramer’s fascinating recollections in the accompanying text, we find that he becomes one of Dylan’s travelling companions. In this role, he’s given both space and time to produce meaningful work. It’s a hallmark of Dylan’s relationships with the producers, musicians and photographers who come into his orbit – once they are admitted, they are allowed to bring their vision with them. Only Alfred Wertheimer on his trips around the country with a young Elvis Presley had such access to a popular star, with similar results – to show the nuts and bolts of the music business and lift the veil at the moment that the cultural plates were shifting.

Listen to any of the session tapes of recent release The Cutting Edge (every single note of music Dylan recorded, complete with false starts and unused takes, throughout 1965, the year of Kramer’s book) and you’ll find that Dylan’s moulding of what’s happening is subtle and understated, only occasionally direct and demanding. And if you met his approval, his world was your oyster. Kramer takes full advantage, producing classic black-and-white reportage backstage, onstage, in cars and cafes.

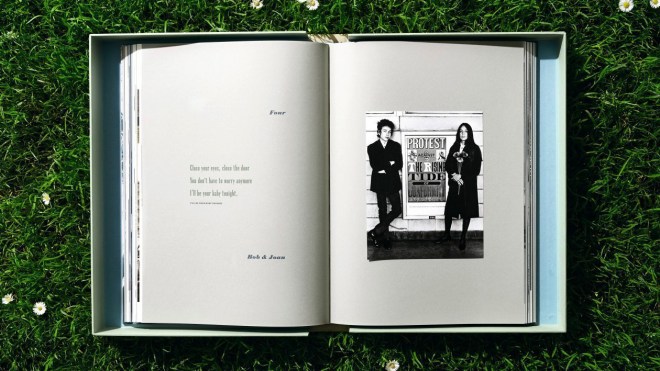

The book, beautifully laid out, is broken into sections (Woodstock / Town Hall / In the Studio / Bob & Joan / Early ’65 / Forest Hills) by lyrics letterpressed onto heavy matt paper, with Kramer’s excellent narrative set in typewriter, an era-specific evocation of the prevailing technology of the time.

The sheer size of the book lets you feel that you’re at a really well-curated exhibition, one where the scaling and sequencing of the images are perfectly judged. The detail drawn out of the gorgeous grain of the 35mm Kodak Tri-X film that Kramer used is wonderful, and the book is a much more satisfying way to see these photographs than as individual prints in a gallery.

The colour film that Kramer shot of Dylan, the cover session for Bringing It All Back Home, one of the two albums he would release in 1965 (the other, Highway 61 Revisited, also had a cover shot by Kramer) sits happily at the centre of the book, in a section called “Intermission”. Kramer’s studio shoots (including a meeting at Kramer’s New York studio that would provide the cover for Dylan’s first book, Tarantula) give a break between the reportage either side and show that his earlier experiences in the studio with Arbus and Halsman served him well.

But first, he needed the persuasive techniques of Bob’s manager to make these shoots happen. After Columbia’s art director, John Berg, refuses to commission the (as he saw it) inexperienced Kramer to shoot the cover of Bringing It All Back Home, Grossman intervenes. “Mr Grossman took us [Dylan and Kramer] to the art director’s office, where he proceeded to make a series of predictions of what bad things would happen [to Berg] if I did not get this assignment.”

Having been present at the recording sessions, Kramer knew that he had to deliver something that related to Dylan’s new direction – and a technique he was working on for a fashion shoot with his 4×5 view camera seemed perfect. It enabled him to make “multiple exposures on one sheet of film while moving, blurring, or keeping sharp parts of any single exposure”, a world away from the fly-on-the-wall 35mm reportage that Kramer had been shooting up to this point.

Arranging Dylan in a room set at Grossman’s Woodstock house, with Sally Grossman draped decoratively on a sofa, Kramer adds elements to make his technique work. “We scoured the house and basement to find things to put in the picture so there would be things to ‘move’ when the camera back was revolved. I wanted to say that Bob Dylan was less a folksinger and more a prince of music. So there in the centre of the turning record is Bob Dylan without an instrument, in this beautiful room, seated with a beautiful woman in a red dress… we were lucky to get one exposure with the cat looking into my lens.” Kramer can’t resist telling us that he and John Berg were nominated for a Grammy Award for best album cover photograph…

Around this time, a new Dylan snaps into view, as the pages turn from images of joking around with old friends to those of Dylan with an early hero, Johnny Cash. Dylan is about to play one of his last acoustic shows and has morphed from the chubby-faced Chaplinesque troubadour to a more angular and focused presence. Over dinner with Cash, he seems to be burning with a particular intensity, fixing Dan Kramer and Cash both with a piercing gaze.

The next stage is about to begin in earnest, and it will lead to the alienation of Dylan’s loyal fanbase. His artistic horizons are widening to take in Pop Art and filmmaking – from Greenwich Village to the Warhol factory was only a matter of a few downtown NY blocks, but in 1965 it was an artistic chasm. On one side, the gruesomely authentic folksters, on the other, the achingly hip (yet blatantly commercial) scenesters. As Dylan moved inexorably across from one to the other, the air was thick with cries of Sell Out! and worse. Kramer finds himself shooting from the inside out.

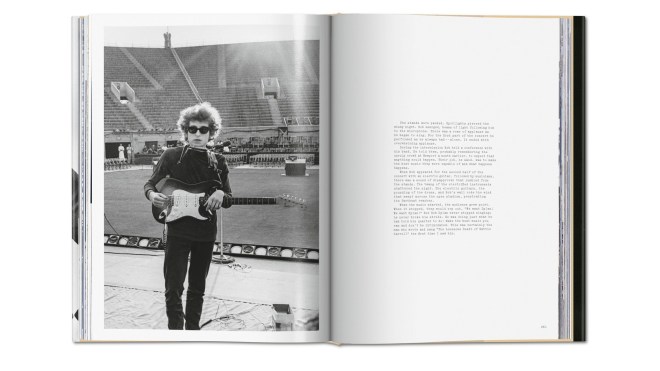

A show at Forest Hills with electric backing will plunge Dylan into a maelstrom that the world of rock has rarely seen, as a performer’s desire to follow his muse sees him branded a Judas and pelted with objects. Visually, Dylan’s look begins to assume the sharp outlines of an icon – even in a close-field blur, with Albert Grossman far away in the stands of the Forest Hills stadium, Dylan is instantly recognisable, entering the period where he would be drawn by Milton Glaser as a rainbow-headed visualisation of the grooviness and excitement of the middle sixties.

And that concert signals the end of Kramer’s travels with Bob. The last shots are of Dylan at one remove from his audience, backlit by blinding spotlights as someone invades the stage, chased by cops. A tour of the US and Europe awaits Dylan, his world accelerating until it culminates in a motorcycle accident that will remove him from the public glare for the following years.

Daniel Kramer moves onto a long and successful career straddling editorial, advertising and motion-picture work, and never photographs Dylan again. And Dylan? Well, he’s still “on the road, heading to another joint…”, not stopping long enough to be pinned down. But we, luckily, have this epic production to linger over, reliving that remarkable year when the times were truly changing.

If you’re receiving the email out, please click on the Date Headline of the page for the full 5 Things experience. It will bring you to the site (which allows you to see the Music Player) and all the links will open in another tab or window in your browser.

The book of Five Things is available from Amazon here.

“He writes with the insight of someone who has inhabited the world of the professional musician but also with the infectious enthusiasm of someone who is a fan like anyone of us. He also comes at the subject from an entirely personal, slightly sideways perspective, with no agenda and no product to sell. It’s entertaining and inspiring in equal measure.”

“A terrific book, stuffed to the gills with snippets of news items and observations all with a musical theme, pulled together by the watchful eye of Martin Colyer… lovingly compiled, rammed with colour photos and interesting stories. Colyer has a good ear for a tune, an eye for the out-of-ordinary and he can write a bit too.”