These are my thoughts after watching Ripley, and as we’re heading back to La Isla Mínima I thought I’d put an Instagram post from our trip last year on Five Things…

{ONE} Steven Zaillian and Robert Elswit’s RIPLEY (Netflix)

If you want to watch this series about an amoral chancer, you will pay for the pleasure. You will be put through the mill. You won’t cast off the deaths like in a two-hour film. You’ll come face-to-face with the real-time problems of murdering someone, especially when those acts weren’t premeditated but arose from a build-up of tension turning into a red mist. If you kill someone on a boat that’s some distance from the shore, this is how it goes down. None of your ideas work, you’re covered in blood, the rope holding the anchor won’t break, and when you do figure that out, it will come to bite you as you fall off the boat and it’s set ploughing a spinning circle, dragging said anchor at speed towards you every rotation. By you, I mean Tom Ripley, of course. The murder and its aftermath last about half the episode — deliberately saying; this may not be your kind of murderous film noi

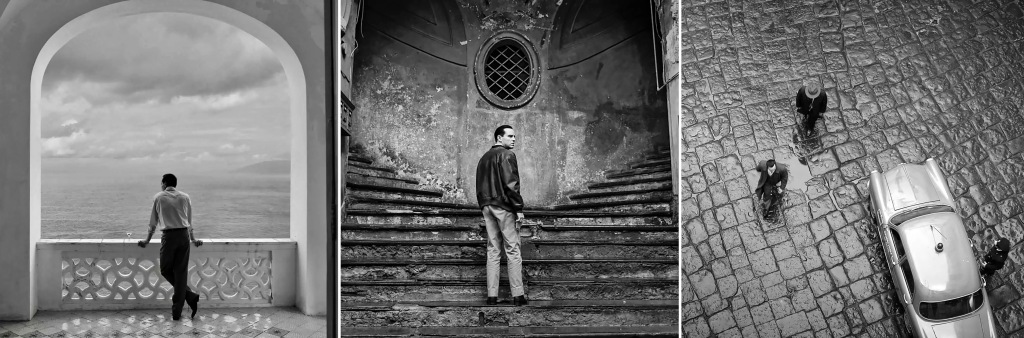

It may also not be your film noir because it has the pace of a film from the 50s. RIPLEY is brave enough to inhabit a world where letters and landlines were the only way to communicate; there were few elevators (but many stairs) in crumbling southern European cities and coastal towns, and life moved at a snail’s pace (appropriately for Highsmith). In today’s world of everything everywhere all at once, this can be a tough watch. Looking at Fallen Idol now, say, or The Third Man, through eyes blasted by the internet or the Marvel Universe, it will drag. But there’s something magnetic in RIPLEY’s formal brilliance — the repeated shots of trains and ferries unhurriedly taking the characters to their next fated appointment — that gets under your skin and keeps you gripped.

It was totally consistent, unlike those series that start with an obvious set of tricks and angles, but by episode four have gone to hell; RIPLEY followed through to the bitter end, a queasy tension permeating its entire length. The directorial vision was so controlled that it was interesting to read an interview with the director and cinematographer in Vanity Fair, where it became obvious that many of the shots were unplanned — most astonishingly in the overhead shot that introduced Dickie and Marge as they lay on the beach, where the shadow of Tom walking up to them falls across the couple.

I’ve never seen a film with so much outrageous patina — the walls, the churches, the leather chairs, the churches, the bench the cat sits on. It was like the casting was also patina-driven: the supporting characters were stunning — you looked forward to the next postman, hotel receptionist, or mafioso being introduced, so you could glory in their fascinating faces, lit in chiaroscuro as they reacted to our (not so charming) grifter. So, hugely recommended if you love the work of Margaret Bourke White or Lee Miller, Carol Reed or Fellini, Gordon Willis or Sven Nyquist. Me, I’m looking for a pair of sunglasses to turn the world monochrome for the summer.

{TWO} LA ISLA MINIMA

We drove to Isla Mayor on a one-way-in-one-way-out road with a bootful of out-of-date medications and a kitchen knife wrapped in a towel. We went there because of a Spanish film we saw, beguiled by its extraordinary setting, and because we love edgelands, those liminal spaces that have their own peculiar atmosphere. The film was called Marshland — in Spanish La Isla Mínima — a policier set in the 80s, but dealing with problems rooted in the Franco era.

Isla Mayor didn’t disappoint. This region, part of a national park, produces 40% of Spain’s rice, is as flat as the fens and consists of miles of paddy fields. As we ate crab tails in a local restaurant, thunder rolled in from the north, the heavens opened, what seemed like a month’s rain fell in half an hour, and everyone was deliriously happy — as a poster on the wall said: “Water is Life, we save the Island, we save an entire people!” The woman who ran the bar dived into the rainy streets to fetch her car to drive a local diner home through the downpour, back in time to bring us our cortados.

Much like the River Po in Italy, where rice is also harvested, the area needs water to exist, and is in crisis in a time of global warming. It’s an hour from Seville, but its wildness feels like another country. When we’re home, we’ll re-watch Marshland, for its spot-on evocation of this eerie landscape. Oh, and the medications? We’d cleared them from our old friend’s boat and no chemist would take them. And the knife? We had some giant Spanish apples that we needed to cut into manageable slices…